Dermatologist explains what the mpox (monkeypox) rash looks like

A new strain of mpox has been found in Africa, Europe, Asia – and now the United States. Because this strain spreads easily and can cause health problems, dermatologists are helping us stay informed by sharing facts about the symptoms and other key information.

Board-certified dermatologist Esther E. Freeman, MD, PhD, FAAD,1 says symptoms of this new strain include:

Fever: This is a common symptom of mpox.

Flu-like symptoms: Headache, muscle aches, back pain, low energy, swollen lymph nodes, sore throat, chills, and exhaustion can occur.

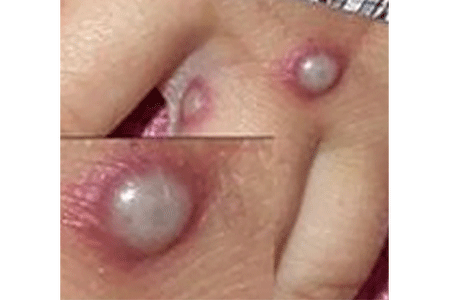

A rash that appears 2-4 days after the above symptoms begin: Often itchy or painful, the rash usually begins on the face and can spread to other parts of the body. This rash can look like chickenpox, shingles, or herpes because it causes spots, bumps, or blisters and may change over time.

“If you have a new, unexplained skin rash or lesion on any part of your body that you think could be mpox, seek medical care immediately,” cautions Dr. Freeman.

What is mpox?

Mpox is a contagious disease caused by a virus. This virus has been infecting humans since 1970, primarily in Africa, where outbreaks have occurred.

Some outbreaks have spread to the United States. In 2022, an mpox outbreak occurred that affected most of the world, including the United States.

People infected with the mpox strain that caused the 2022 outbreak tend to develop a few pox-like lesions on their skin, as shown here.

During previous mpox outbreaks, people often had widespread lesions.

The mpox strain that caused the 2022 outbreak is still in the United States. However, the number of new infections is low. Ten or fewer people become infected each week.

How do you get mpox?

You develop mpox through close contact with an infected person or animal. Here’s how this happens:

An infected person: If someone has mpox, you can catch it if you:

Touch the rash or scabs or have intimate contact. This is the most common way mpox spreads.

Handle an object that an infected person has used like unwashed clothing or bedding.

An infected animal: Animals infected with mpox are found in central or western Africa, where this virus is endemic (there all the time). Most of the infected animals are wild rodents like rope squirrels and dormice.

You can get mpox from an animal infected with the virus if you:

Are bit or scratched by the animal

Handle an infected animal (even a dead one)

Eat an infected animal

Use a product like a cream or powder made from an infected animal

Getting vaccinated can reduce at-risk people from getting mpox

The vaccine used to prevent smallpox is also used to prevent mpox. If you have received this vaccine:

You have less risk of getting mpox. The vaccine is about 85% effective at preventing mpox.

Mpox tends to be less serious if you develop it. This means less risk of developing severe disease or being hospitalized.

Who should receive the mpox vaccine?

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends that people in the United States who are at risk for mpox receive two doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine. At-risk people include those who have been in contact with someone who has mpox.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved the JYNNEOS vaccine to prevent both smallpox and mpox.

If you have risk factors that make you eligible for getting vaccinated against mpox and have never had mpox, the CDC recommends that you get:

Both doses of the JYNNEOS vaccine, waiting 28 days between doses.

The second dose of JYNNEOS if you’ve only received one dose. It’s never too late to get the second dose.

Right now, getting more than two doses (a booster) isn’t recommended.

After getting vaccinated, it takes several weeks for your body to develop immunity. That’s why the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that you take measures to prevent mpox for weeks after you receive the vaccine.

People who’ve had mpox don’t need to get vaccinated.

Most rashes that dermatologists are seeing at this time are not caused by mpox

Still, it’s important for you to be aware of mpox and get medical care if you develop a new rash with an unknown cause. Just be sure to call ahead before going to a medical office since mpox is contagious.

How do dermatologists know mpox is causing a rash?

"While the mpox rash can be mistaken for chickenpox, shingles, or herpes, there are differences between these rashes," says Dr. Freeman. A board-certified dermatologist has the expertise and training to spot the differences, so you receive an accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

If mpox is a likely cause, your dermatologist will swab your rash and send the swab to a lab. At the lab, a test known as a PCR (polymerase chain reaction) test will be performed. The results from the PCR test will indicate whether the swab contains the mpox virus.

How long does mpox last?

Most people have mpox for 2 to 4 weeks. That’s the amount of time it takes for the disease to run its course.

Until the rash and bumps go away, a person who has mpox is contagious and can spread the virus to others.

What should I do if I have symptoms of mpox?

Dr. Freeman notes, "Not every new rash is mpox. However, if you do think you have mpox, it’s important to see your doctor quickly. Patients who delay getting medical attention may be diagnosed later when fewer treatment options are available. Waiting also means that you can expose more people to the virus, so family and others may develop mpox."

How is mpox treated?

For some people, the disease can run its course. However, people at risk of developing severe disease may receive treatment. Some antiviral medications are being used to treat people when the PCR test shows that they have mpox. There is currently no specific treatment approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mpox.

If you are diagnosed with mpox, proper skin care can help prevent the disease from spreading to other parts of your body and reduce the risk of scarring. To see the skin care that dermatologists recommend, go to Mpox rash: Dermatologists' tips for treating your skin.

1 Dr. Freeman is the Director, Global Health Dermatology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School; Associate Director, Center for Global Health, Massachusetts General Hospital; and a member of the American Academy of Dermatology’s Mpox Task Force.

Images

Images 1, 2: Produced with permission from ©DermNet www.dermnetnz.org 2024.

Image 3: Used with permission of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This image is also available on the CDC website, and use of this image does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the U.S. Government, Department of Health and Human Services, or Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Images 4,5: Getty Images

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

“Mpox in the United States and Around the World: Current Situation.” Last updated November 16, 2024. Last accessed November 18, 2024.

“U.S. case trends: Data as reported to CDC as of November 1, 2024.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA):

“Illegally sold monkeypox products.” Content current as of January 31, 2024. Last accessed November 4, 2024.

“JYNNEOS.” Page last updated October 22, 2024. Last accessed November 4, 2024.

“Mpox.” Page last updated October 1, 2024. Last accessed November 4, 2024.

World Health Organization. “Mpox.” Page last updated October 16, 2024. Last accessed October 31, 2024.

Written by:

Paula Ludmann, MS

Reviewed by:

Esther Ellen Freeman, MD, PhD, FAAD

George J. Hruza, MD, MBA, FAAD

William Warren Kwan, MD, FAAD

J. Klint Peebles, MD, FAAD

Adrian O. Rodriguez, MD, FAAD

Misha Rosenbach, MD, FAAD

Last updated: 11/18/24

Atopic dermatitis: More FDA-approved treatments

Atopic dermatitis: More FDA-approved treatments

Biosimilars: 14 FAQs

Biosimilars: 14 FAQs

How to trim your nails

How to trim your nails

Relieve uncontrollably itchy skin

Relieve uncontrollably itchy skin

Fade dark spots

Fade dark spots

Untreatable razor bumps or acne?

Untreatable razor bumps or acne?

Tattoo removal

Tattoo removal

Scar treatment

Scar treatment

Free materials to help raise skin cancer awareness

Free materials to help raise skin cancer awareness

Dermatologist-approved lesson plans, activities you can use

Dermatologist-approved lesson plans, activities you can use

Find a Dermatologist

Find a Dermatologist

What is a dermatologist?

What is a dermatologist?